Why would one want to generalize notions such as convergence and continuity to a setting even more abstract than metric spaces?

Topology deals with the relative position of objects to each other and their features. It is not about their concrete length, volume, and so on. Hence, topological features will not change if continuous transformations are applied to these objects. That is, topological features are preserved under stretching, squeezing, bending, and so on but they are not preserved under non-continuous transformations such as tearing apart, cutting and so on. Objects such as a circle, a rectangle and a triangle are from a topological point of view “equal” / homeomorphic even though the shapes are geometrically rather different.

What features are therefore of interest such that it is worth studying topology?

Assume that ![]() is a closed curve, i.e. a circle, a rectangle, a triangle or something like we can see in the graph above. As long as we transform a shape

is a closed curve, i.e. a circle, a rectangle, a triangle or something like we can see in the graph above. As long as we transform a shape ![]() in a continuous fashion, the relative positions of the points

in a continuous fashion, the relative positions of the points ![]() and

and ![]() will be similar: for instance, points that have been inside of

will be similar: for instance, points that have been inside of ![]() will still be inside after the continuous transformation. Points that have been on the boundary will still be on the boundary.

will still be inside after the continuous transformation. Points that have been on the boundary will still be on the boundary.

Hence, the generalization of continuity and the concept of convergence (i.e. points being ‘close to each other’) are the two most characterizing features in topological spaces.

However, convergence and continuity in a metric space ![]() were based on a notion of a distance function

were based on a notion of a distance function ![]() for points

for points ![]() . Set-theoretic topology generalizes the features of topological metric space and ought to be based on an axiomatized notion of “closeness“.

. Set-theoretic topology generalizes the features of topological metric space and ought to be based on an axiomatized notion of “closeness“.

This post is based on the literature [1] to [5]. For English-speaking beginners, [5] is recommended. The German lecture notes [3] is also a good introduction to topology.

Topology on a Set

The term “topology on a set” is based on an axiomatic description of so-called “open sets” with respect to some set-theoretic operators. It will turn out, that a topology is a set that has just enough structure to meaningful speak of convergence and continuous functions on it.

Open Sets

Definition 1.1 (Topological Space)

A topological space is a pair ![]() , where

, where ![]() is a set and

is a set and ![]() is a family of subsets that satisfies

is a family of subsets that satisfies

(i) ![]() ;

;

(ii) ![]() if

if ![]() for an arbitrary index set

for an arbitrary index set ![]() ;

;

(iii) ![]() if

if ![]() for a finite index set

for a finite index set ![]() .

.

![]()

Let ![]() — short

— short ![]() — be a topological space in this post.

— be a topological space in this post.

The following video provides a rather unorthodox way of thinking about a topology. However, it might help to get a heuristic understanding. The connection between metrics and topologies is also mentioned.

Some examples will further support the understanding.

Example 1.1 (Topologies)

(a) Let ![]() be a set and

be a set and ![]() then

then ![]() is the so-called trivial, chaotic or indiscrete topology. The only open sets of the trivial topology are

is the so-called trivial, chaotic or indiscrete topology. The only open sets of the trivial topology are ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

(b) The power set ![]() of a set

of a set ![]() is the so-called discrete topology. In this topology every subset is open.

is the so-called discrete topology. In this topology every subset is open.

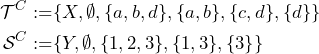

(c) There are four topologies on the set ![]() , i.e.

, i.e. ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

It is still an open problem, which is related to combinatorics and lattice theory, to find a simple formula for the number of topologies on a finite set.

(d) Let ![]() be a topological space, and let

be a topological space, and let ![]() . The relative topology on

. The relative topology on ![]() (or the topology inherited from

(or the topology inherited from ![]() ) is the collection

) is the collection

![]()

of subsets of ![]() . It is clearly a topology on

. It is clearly a topology on ![]() . The space

. The space ![]() is then called a subspace of

is then called a subspace of ![]() .

.

(e) Let ![]() be a non-empty infinite set and

be a non-empty infinite set and ![]() be the family of open sets. Then

be the family of open sets. Then ![]() is the so-called finite complement topology. First note, that an element

is the so-called finite complement topology. First note, that an element ![]() ,

, ![]() is of infinite cardinality. Think about what happens if we remove finitely many elements from an infinite set.

is of infinite cardinality. Think about what happens if we remove finitely many elements from an infinite set.

Apparently, ![]() since

since ![]() can be considered as finite.

can be considered as finite. ![]() due to the definition of the set

due to the definition of the set ![]() even though

even though ![]() is not finite.

is not finite.

The union of arbitrary open as well as the intersection of a finitely many open sets are open again. The corresponding proof employs De Morgan’s Laws.

(f) Let ![]() be a non-empty countable set and

be a non-empty countable set and ![]() be the family of open sets. Then

be the family of open sets. Then ![]() is the so-called countable complement topology.

is the so-called countable complement topology.

Apparently, ![]() since

since ![]() is countable and

is countable and ![]() due to the definition. The corresponding proofs of the union and intersection of open sets also employs De Morgan’s Laws.

due to the definition. The corresponding proofs of the union and intersection of open sets also employs De Morgan’s Laws.

![]()

According to Proposition 1.1 – Fundamentals of Topology & Metric Spaces, the set ![]() of all open sets in a metric space

of all open sets in a metric space ![]() complies with the definition of a topology.

complies with the definition of a topology.

Definition 1.2 (Induced & Equivalent Topology)

A topology ![]() induced by a metric space

induced by a metric space ![]() is defined as the set

is defined as the set ![]() of all open sets in

of all open sets in ![]() .

.

Two metrics ![]() and

and ![]() on the same basic set

on the same basic set ![]() are called topologically equivalent if

are called topologically equivalent if ![]() .

.

![]()

Let us define a very basic but important term.

Definition 1.3 (Neighborhood)

A neighborhood ![]() of a point

of a point ![]() in a topological space

in a topological space ![]() is any set containing

is any set containing ![]() as well as an open set

as well as an open set ![]() of

of ![]() , i.e.

, i.e. ![]() .

.

![]()

Some examples will improve the understanding.

Example 1.2 (Metrizable and Equivalent Topologies)

(a) If ![]() is a metric space and

is a metric space and ![]() is the set of all open sets, then

is the set of all open sets, then ![]() is a topology. The topology

is a topology. The topology ![]() does not depend on the particular metric

does not depend on the particular metric ![]() since the proof of the referred Proposition 1.1 can also be done using the term neighborhood instead of the distance function. Hence, any metric on

since the proof of the referred Proposition 1.1 can also be done using the term neighborhood instead of the distance function. Hence, any metric on ![]() equivalent to

equivalent to ![]() yields the same topology. Topological spaces of this kind are called metrizable.

yields the same topology. Topological spaces of this kind are called metrizable.

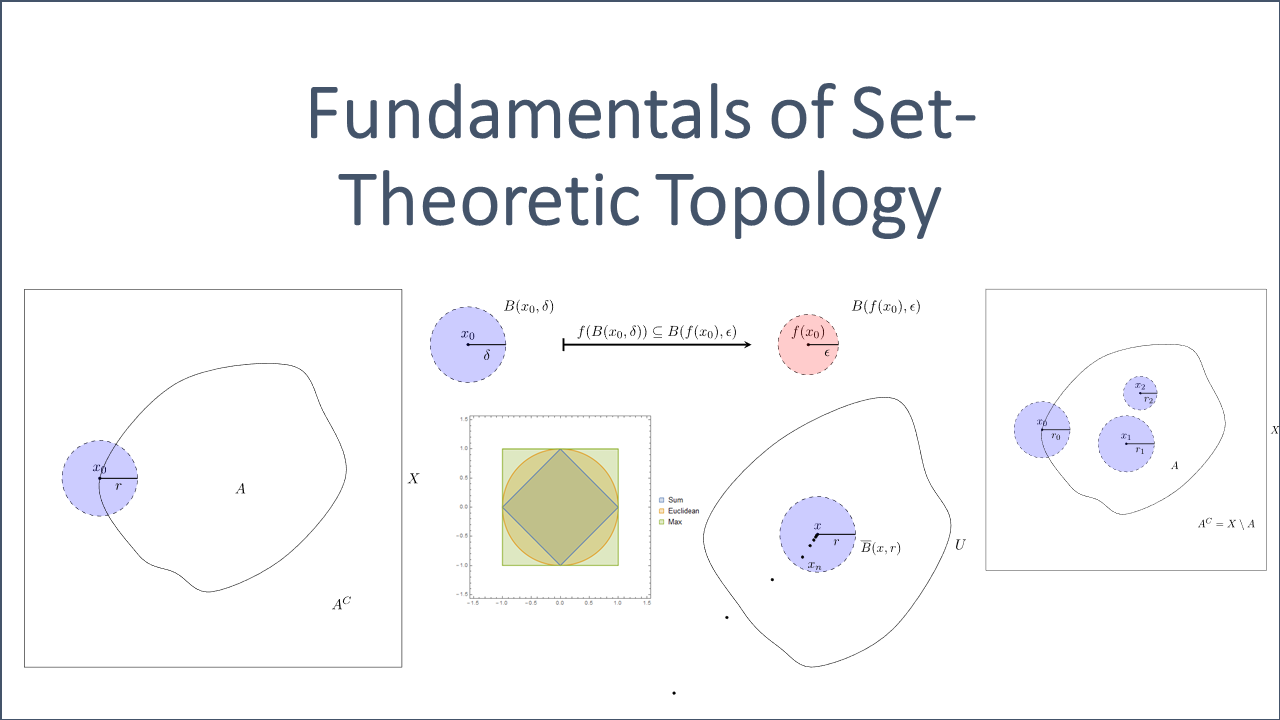

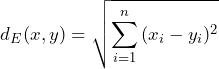

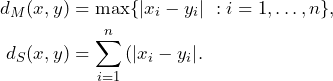

(b) Let us consider ![]() equipped with the natural topology by taking the topology

equipped with the natural topology by taking the topology ![]() induced by the Euclidean metric

induced by the Euclidean metric

with ![]() and

and ![]() . Instead of using the Euclidean metric, we could also employ the following distance functions:

. Instead of using the Euclidean metric, we could also employ the following distance functions:

All three induced topologies would be equivalent, i.e. ![]() since

since

![]()

for all ![]() . The corresponding unit open balls centered at

. The corresponding unit open balls centered at ![]() are illustrated as follows.

are illustrated as follows.

An open ball ![]() with

with ![]() as shown in Fig. 1 is actually a set of points where each point has a distance of max. 1 to the origin

as shown in Fig. 1 is actually a set of points where each point has a distance of max. 1 to the origin ![]() . This, however, is nothing but the corresponding norm

. This, however, is nothing but the corresponding norm ![]() . For instance, the point

. For instance, the point ![]() is not an element of the unit ball induced by

is not an element of the unit ball induced by ![]() since

since ![]() . However, the same point

. However, the same point ![]() is element of the unit balls induced by

is element of the unit balls induced by ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

From a topological point of view the shapes in Fig. 1 are all equivalent.

![]()

Closed Sets

Directly linked via the definition to open sets and equivalent in their explanatory power are closed sets.

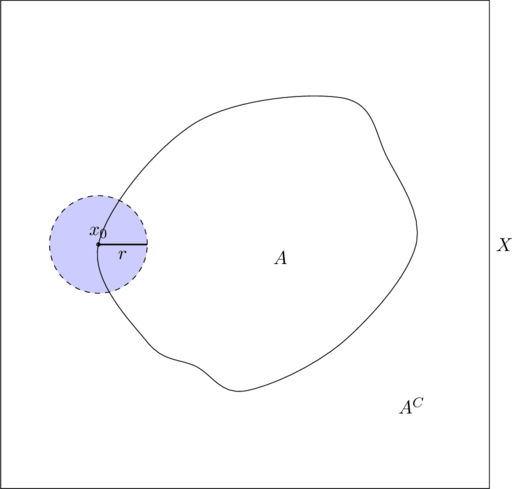

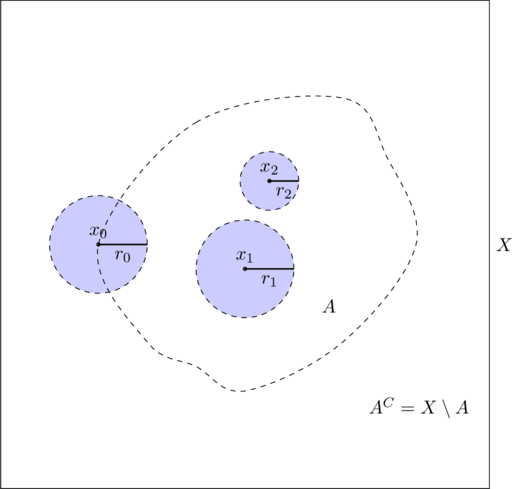

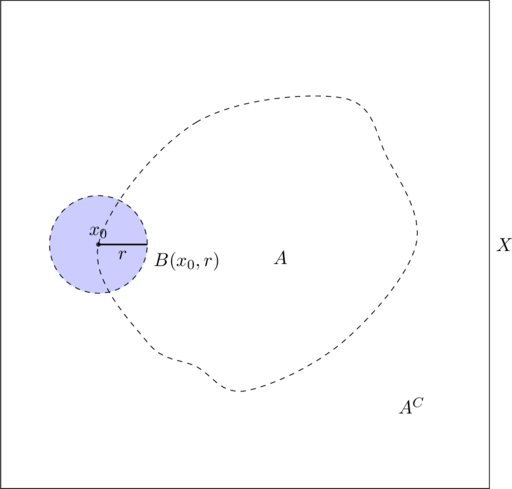

A set ![]() is open in an Euclidean metric space if and only if for every

is open in an Euclidean metric space if and only if for every ![]() an open ball

an open ball ![]() exists such that

exists such that ![]() . Let us therefore consider the situation in the real plane

. Let us therefore consider the situation in the real plane ![]() employing the topology induced by the Euclidean metric. The open balls

employing the topology induced by the Euclidean metric. The open balls ![]() and

and ![]() are both contained in

are both contained in ![]() .

.

However, the open ball ![]() cannot be fully contained in

cannot be fully contained in ![]() no matter how small we pick

no matter how small we pick ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() is not an element of the open set

is not an element of the open set ![]() .

.

Let us now study sets ![]() whenever

whenever ![]() is open.

is open.

Definition 1.4 (Closed Sets)

A set ![]() is called closed in

is called closed in ![]() if

if ![]() is open in

is open in ![]() .

.

![]()

The definition actually tells us that one just needs to consider the complement set ![]() to figure whether the set

to figure whether the set ![]() is closed.

is closed.

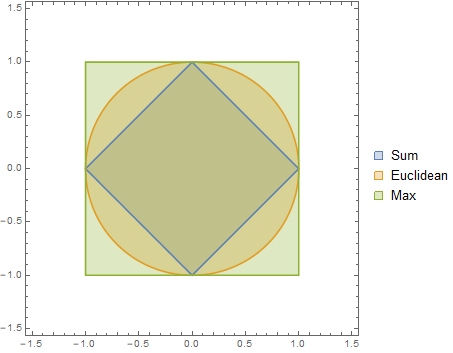

Example 1.3 (Closed Sets)

(a) Let ![]() b a metric space. Then

b a metric space. Then ![]() is closed in

is closed in ![]() if and only if

if and only if ![]() is closed in

is closed in ![]() . For instance, an arbitrary open ball

. For instance, an arbitrary open ball ![]() with

with ![]() is open. Thus, the set

is open. Thus, the set ![]() is closed. The situation for

is closed. The situation for ![]() and the Euclidean topology is sketched in the next figure.

and the Euclidean topology is sketched in the next figure.

(b) The sets ![]() are not only open but also closed for any topological space

are not only open but also closed for any topological space ![]() since

since ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

The topological space is trivial / indiscrete if and only if these two sets are the only closed sets in ![]() . The closed sets of the indiscrete / trivial topology are the complements of the open sets. Hence, the closed sets are also

. The closed sets of the indiscrete / trivial topology are the complements of the open sets. Hence, the closed sets are also ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

(c) The topology ![]() is discrete if and only if every subset

is discrete if and only if every subset ![]() is closed. This can be seen by

is closed. This can be seen by ![]() .

.

(d) The subset ![]() of

of ![]() is closed because its complement

is closed because its complement ![]() is open. Similarly,

is open. Similarly, ![]() is closed, because its complement

is closed, because its complement ![]() is open.

is open.

The subsets ![]() of

of ![]() are neither open nor closed.

are neither open nor closed.

(e) In the finite complement topology on an infinite set ![]() , the closed sets consists of

, the closed sets consists of ![]() itself and all finite subsets of

itself and all finite subsets of ![]() . This follows directly from the definition of the set

. This follows directly from the definition of the set ![]() as set out in Example 1.1 (e). According to this definition, the sets

as set out in Example 1.1 (e). According to this definition, the sets ![]() with

with ![]() need to be finite with the exception of

need to be finite with the exception of ![]() .

.

![]()

Let us characterize closed sets.

Proposition 1.1: (Characterization of Closed Sets)

(1) The set ![]() of all closed sets of

of all closed sets of ![]() complies with the following conditions:

complies with the following conditions:

(i) ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

(ii) ![]() implies

implies ![]() .

.

(iii) ![]() implies

implies ![]() .

.

(2) Let ![]() be a family of sets that complies with (i), (ii) and (iii) then there exists a topology

be a family of sets that complies with (i), (ii) and (iii) then there exists a topology ![]() , such that

, such that ![]() is the set of all closed sets in

is the set of all closed sets in ![]() .

.

Proof.

(1) This follows directly from the definitions and applying the rules ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() as well as

as well as ![]() .

.

(2) The family of closed sets ![]() fully determines the topology

fully determines the topology ![]() on the same basic set

on the same basic set ![]() since

since ![]() . Its existence follows from the fact that

. Its existence follows from the fact that ![]() actually is a topology but this is clear given (1).

actually is a topology but this is clear given (1).

![]()

The family of closed sets of a topology could also be used to define a topological space, i.e. the set of all closed sets contains exactly the same information as the set of all open sets that actually define the topology.

Points, that lie at the boundary between ![]() and

and ![]() , are crucial for the understanding and distinction of open and closed sets. The intuitive idea of a boundary point

, are crucial for the understanding and distinction of open and closed sets. The intuitive idea of a boundary point ![]() is depicted in the next figure.

is depicted in the next figure.

Interior, Closure & Boundary

The points that lie close to both the “inside” and the “outside” of the set ![]() play an important role. However, before we can define a boundary point, we need to clarify what is meant by “inside” and “outside”.

play an important role. However, before we can define a boundary point, we need to clarify what is meant by “inside” and “outside”.

Definition 1.5 (Interior & Closure)

Let ![]() be a topology. The interior of

be a topology. The interior of ![]() is defined as the union of all open sets contained in

is defined as the union of all open sets contained in ![]() , i.e.

, i.e.

![]()

The closure of ![]() is defined as the intersection of all closed sets containing

is defined as the intersection of all closed sets containing ![]() , i.e.

, i.e.

![]()

![]()

Apparently, the interior of ![]() is open and a subset of

is open and a subset of ![]() while the closure of

while the closure of ![]() is closed and contains

is closed and contains ![]() . Thus, the following set relation is valid for any set

. Thus, the following set relation is valid for any set ![]() in a topological space:

in a topological space:

![]()

The following theorem provides some useful relationships. However, we will not prove all of the statements and refer to section 2.1 in [5], for instance.

Theorem 1.1 (Properties of Closure and Interior)

For sets ![]() in a topological space

in a topological space ![]() , the following statements hold:

, the following statements hold:

(i) If ![]() is an open set in

is an open set in ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() Int

Int![]() ;

;

(ii) If ![]() is a closed set in

is a closed set in ![]() and

and ![]() , then Cl

, then Cl![]() ;

;

(iii) If ![]() then Int

then Int![]() Int

Int![]() and Cl

and Cl![]() Cl

Cl![]() ;

;

(iv) ![]() is open if and only if Int

is open if and only if Int![]() ;

;

(v) ![]() is closed if and only if Cl

is closed if and only if Cl![]() .

.

Proof. (i) Since Int![]() is the union of all of the open sets that are contained in

is the union of all of the open sets that are contained in ![]() , it follows that

, it follows that ![]() is one of the sets making up this union and therefore is a subset of the union. That is,

is one of the sets making up this union and therefore is a subset of the union. That is, ![]() Int

Int![]() .

.

(ii) Since Cl![]() is the intersection of all of the closed sets that contain

is the intersection of all of the closed sets that contain ![]() , it follows that

, it follows that ![]() is one of the sets making up this intersection and therefore is Cl

is one of the sets making up this intersection and therefore is Cl![]() is contained in

is contained in ![]() . That is, Cl

. That is, Cl![]() .

.

(iii) Since ![]() , Int

, Int![]() is an open set contained in

is an open set contained in ![]() . According to (i) every open set contained in

. According to (i) every open set contained in ![]() is contained in Int

is contained in Int![]() . Therefore, Int

. Therefore, Int![]() Int

Int![]() . One can use (ii) to show the second statement of (iii).

. One can use (ii) to show the second statement of (iii).

(v) If ![]() Int

Int![]() , then

, then ![]() is an open set since by definition Int

is an open set since by definition Int![]() is an open set. Now assume that

is an open set. Now assume that ![]() is open. We show that

is open. We show that ![]() Int

Int![]() . First, Int

. First, Int![]() by definition of Int

by definition of Int![]() . Furthermore, since

. Furthermore, since ![]() is an open set contained in

is an open set contained in ![]() , it follows by (i) that

, it follows by (i) that ![]() Int

Int![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() Int

Int![]() as we wished to show.

as we wished to show.

![]()

Example 1.4 (Closure and Interior)

(a) Consider ![]() in the standard topology on

in the standard topology on ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() and Int

and Int![]() .

.

(b) Consider ![]() as a subset of

as a subset of ![]() with the discrete topology

with the discrete topology ![]() . Since all subsets are open and closed we have Int

. Since all subsets are open and closed we have Int![]() Cl

Cl![]() .

.

(c) Consider ![]() in the finite complement topology on

in the finite complement topology on ![]() . Since a closd set in this topology is either

. Since a closd set in this topology is either ![]() or finite, it is clear that only

or finite, it is clear that only ![]() is a closed set containing the infinite set

is a closed set containing the infinite set ![]() . Hence, Cl

. Hence, Cl![]() . The open sets are precisely the empty set and the cofinite subsets, i.e., the subsets whose complements are finite subsets of

. The open sets are precisely the empty set and the cofinite subsets, i.e., the subsets whose complements are finite subsets of ![]() . Hence, Int

. Hence, Int![]() since there are no open sets in

since there are no open sets in ![]() contained in

contained in ![]() .

.

![]()

The last example highlights that not only the actual sets matter but also the sourounding topology. The next theorem provides a simple means for determining when a particular point ![]() is in the interior or in the closure of a given set

is in the interior or in the closure of a given set ![]() .

.

Theorem 1.2 (Closure, Interior and Open Sets)

Let ![]() be a topological space,

be a topological space, ![]() be a subset of

be a subset of ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

(i) Then ![]() Int

Int![]() if and only if there exists an open set

if and only if there exists an open set ![]() such that

such that ![]() ;

;

(ii) Then ![]() Cl

Cl![]() if and only if every open set containing

if and only if every open set containing ![]() intersects

intersects ![]() .

.

Proof. (i) First, suppose that there exists an open set ![]() such that

such that ![]() . Then, since

. Then, since ![]() is open and contained in

is open and contained in ![]() , it follows that

, it follows that ![]() Int

Int![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() Int

Int![]() .

.

Next, if ![]() Int

Int![]() , and we set

, and we set ![]() Int

Int![]() , it follows that

, it follows that ![]() is an open set such that

is an open set such that ![]() .

.

(ii) Considering the contrapositive: ![]() Cl

Cl![]() if and only if there is one neighborhood that does not intersect

if and only if there is one neighborhood that does not intersect ![]() . If

. If ![]() Cl

Cl![]() then the set

then the set ![]() Cl

Cl![]() is open and does contain

is open and does contain ![]() , which is as claimed in the contrapositive.

, which is as claimed in the contrapositive.

Conversely, if there is a neighborhood ![]() of

of ![]() which does not intersects

which does not intersects ![]() , then its complement

, then its complement ![]() is a closed set that contains

is a closed set that contains ![]() . By definition of the closure Cl

. By definition of the closure Cl![]() , the set

, the set ![]() must contain Cl

must contain Cl![]() . Since

. Since ![]() it follows that

it follows that ![]() Cl

Cl![]() . Contraction.

. Contraction.

![]()

Theorem 1.3 (Relations of Closure and Interior)

For sets ![]() in a topological space

in a topological space ![]() , the following statements hold:

, the following statements hold:

(i) Int![]() =

= ![]() Cl

Cl![]() ;

;

(ii) Cl![]() =

= ![]() Int

Int![]() ;

;

(iii) Int![]() Int

Int![]() Int

Int![]() , and in general equality does not hold;

, and in general equality does not hold;

(iv) Int![]() Int

Int![]() = Int

= Int![]() .

.

Proof. Refer to Theorem 2.6 in [5] and to Folgerung 1.2.25 in [3].

![]()

Now, we have all ingredients to define the so-called boundary.

Definition 1.6 (Boundary Set & Points)

Let ![]() ,

, ![]() . The boundary of

. The boundary of ![]() , denoted by

, denoted by ![]() . A point of

. A point of ![]() is called boundary point.

is called boundary point.

![]()

There are situations that challenge or defy our intuitive understanding of boundary sets. For example, what is the boundary of ![]() as a subset of

as a subset of ![]() in the standard topology?

in the standard topology?

Example 1.4 (Boundary Sets & Points)

(a) Consider ![]() in the standard topology on

in the standard topology on ![]() . The boundary set

. The boundary set ![]() equals

equals ![]() .

.

(b) Consider ![]() in the standard topology on

in the standard topology on ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() , and

, and ![]() , it follows that

, it follows that ![]() . The entire real line is therefore the boundary of the rational numbers, which makes sense. Every real number is arbitrarily close to the set of rational numbers and to its complement, the set of irrational numbers.

. The entire real line is therefore the boundary of the rational numbers, which makes sense. Every real number is arbitrarily close to the set of rational numbers and to its complement, the set of irrational numbers.

(c) Let ![]() in

in ![]() with the discrete topology

with the discrete topology ![]() . That is, every subset is open and closed at the same time. Hence,

. That is, every subset is open and closed at the same time. Hence, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

![]()

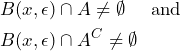

In a metric space, a point ![]() is a boundary point of

is a boundary point of ![]() if

if

(1)

for all ![]() .

.

Let us now prove the generalized statement about boundary sets.

Proposition 1.2 (Characterization of Boundary Points)

Let ![]() be a subset of a topological space

be a subset of a topological space ![]() and let

and let ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() if and only if every neighborhood of

if and only if every neighborhood of ![]() intersects both

intersects both ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Proof. Suppose ![]() , then

, then ![]() and

and ![]() due to the definition. Since

due to the definition. Since ![]() , it follows that every neighborhood of

, it follows that every neighborhood of ![]() intersects

intersects ![]() . Note that a neighborhood of

. Note that a neighborhood of ![]() contains

contains ![]() . Furthermore, since

. Furthermore, since ![]() , it follows that every neighborhood of

, it follows that every neighborhood of ![]() intersects

intersects ![]() . Thus, every neighborhood of

. Thus, every neighborhood of ![]() intersects

intersects ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Now suppose that every neighborhood of ![]() intersects

intersects ![]() and

and ![]() . It follows that

. It follows that ![]() and

and ![]() Cl

Cl![]() . By

. By

![]()

Theorem 1.4 (Open Sets and Neighborhoods)

Let ![]() be a topological space and let

be a topological space and let ![]() be a subset of

be a subset of ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() is open in

is open in ![]() if and only if for each

if and only if for each ![]() , there is a neighborhood

, there is a neighborhood ![]() of

of ![]() such that

such that ![]() .

.

Proof. First, suppose that ![]() is open in

is open in ![]() and

and ![]() . If we let

. If we let ![]() then

then ![]() is a neighborhood of

is a neighborhood of ![]() for which

for which ![]() .

.

Now suppose that for every ![]() there exists a neighborhood

there exists a neighborhood ![]() of

of ![]() such that

such that ![]() . Since we know that the union

. Since we know that the union ![]() of open sets is open, the assertion follows.

of open sets is open, the assertion follows.

![]()

The set ![]() can be contained in

can be contained in ![]() or in

or in ![]() :

:

- If all boundary points

are outside of

are outside of  , i.e. if

, i.e. if  , then it is an open set.

, then it is an open set. - If all boundary points are contained within the set, then it is a closed set.

Proposition 1.2 (Closure and Open Sets)

Let ![]() be a topological space,

be a topological space, ![]() be a subset of

be a subset of ![]() , and

, and ![]() be an element of

be an element of ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() if and only if every open set containing

if and only if every open set containing ![]() intersects

intersects ![]() .

.

Proof. The closure ![]() is the smallest closed set containing

is the smallest closed set containing ![]() as a subset. Let

as a subset. Let ![]() and let

and let ![]() be an open neighborhood of

be an open neighborhood of ![]() . If

. If ![]() then

then ![]() , and the latter set is closed (by definition), which leads to a contradiction. So

, and the latter set is closed (by definition), which leads to a contradiction. So ![]() .

.

![]()

The property of the closure hitting an open set is so important that usually a new term is defined. Note, however, that we will not further use it in this post.

Definition 1.7 (Adherent Point)

Let ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() . The point

. The point ![]() is called adherent point if every open

is called adherent point if every open ![]() of

of ![]() has a non-empty intersection with

has a non-empty intersection with ![]() , i.e.

, i.e. ![]() for all

for all ![]() with

with ![]() .

.

![]()

Let us come back to Example 1.2 (a) – considering this example we could ask whether every topological space is metrizable?

The answer is no, and the root-cause is that topological spaces have different types of separation properties.

Separation Properties

A metric enables us to separate points in a metric space since any two distinct points have a strictly positive distance. In general topological spaces, separating points from each other is more subtle.

Hausdorff Space

Hausdorff spaces and the Hausdorff condition are named after Felix Hausdorff, one of the founders of topology. Let us first check out the formal definition.

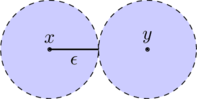

Definition 2.1: (Hausdorff Space, ![]() Spaces)

Spaces)

A topological space ![]() is a Hausdorff or

is a Hausdorff or ![]() -space if, for any pair of distinct points

-space if, for any pair of distinct points ![]() ,

, ![]() there are disjoint open sets

there are disjoint open sets ![]() with

with ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

![]()

Every Euclidean space is Hausdorff since we can use the Euclidean metric to separate two distinct points. The following video outlines the Hausdorff condition and it provides a simple example of a Hausdorff space.

Example 2.1 (Metric Space is Hausdorff)

(a) Let ![]() be a metric space, and let

be a metric space, and let ![]() be such that

be such that ![]() . It follows that

. It follows that ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() and

and ![]() . Then,

. Then, ![]() is Hausdorff since

is Hausdorff since ![]() .

.

(b) Consider the indiscrete / trivial topology ![]() with

with ![]() . By definition, the only neighborhood of any two points

. By definition, the only neighborhood of any two points ![]() is the entire set

is the entire set ![]() . Thus, every neighborhood of

. Thus, every neighborhood of ![]() will contain

will contain ![]() and vice verca. It follows that the indiscrete / trivial topology is neither Hausdorff nor metrizable.

and vice verca. It follows that the indiscrete / trivial topology is neither Hausdorff nor metrizable.

![]()

In a Hausdorff space, distinct points can be separated by open sets.

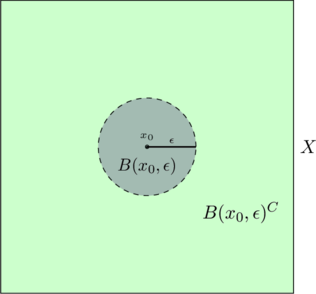

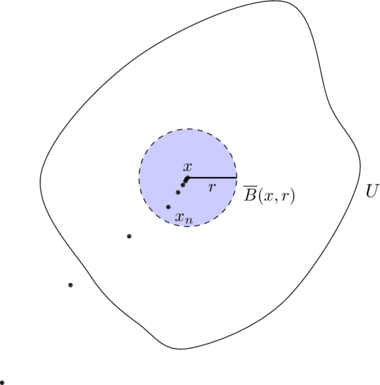

The situation in ![]() along with the topology implied by the Euclidean metric is illustrated in the graph above. For two distinct points

along with the topology implied by the Euclidean metric is illustrated in the graph above. For two distinct points ![]() , we take half (or less) the distance to define

, we take half (or less) the distance to define ![]() to come up with two distinct open balls, that can also be seen as disjoint neighborhoods.

to come up with two distinct open balls, that can also be seen as disjoint neighborhoods.

Proposition 2.1: (Subset of ![]() -spaces)

-spaces)

Let ![]() be a topological Hausdorff space. Then, each subset

be a topological Hausdorff space. Then, each subset ![]() of a Hausdorff space is Hausdorff.

of a Hausdorff space is Hausdorff.

Proof. Let ![]() be in

be in ![]() . The space being Hausdorff, let

. The space being Hausdorff, let ![]() and

and ![]() be the two open separating sets as required in Definition 1.1. Then

be the two open separating sets as required in Definition 1.1. Then ![]() as well as

as well as ![]() are open since the difference of two open sets is open. In addition,

are open since the difference of two open sets is open. In addition, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

![]()

Spaces with Weaker Separation Property

The following separation properties are weaker than the Hausdorff (![]() -) condition. This is also indicated by the index of the corresponding names of the separation axioms (from

-) condition. This is also indicated by the index of the corresponding names of the separation axioms (from ![]() to

to ![]() ).

).

Definition 2.2. (![]() Space)

Space)

A topological space ![]() is called a

is called a ![]() – or Kolmogorov space if, for any

– or Kolmogorov space if, for any ![]() with

with ![]() , there is an open set

, there is an open set ![]() with

with ![]() and

and ![]() or

or ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

![]()

The most striking difference between a Hausdorff / ![]() – and

– and ![]() -space is that only one open set

-space is that only one open set ![]() , that contains only one of two distinct points, is required to fulfill the definition of a

, that contains only one of two distinct points, is required to fulfill the definition of a ![]() -space. Apparently, every

-space. Apparently, every ![]() -space is also a

-space is also a ![]() -space.

-space.

Example 2.2:

(a) Let ![]() be any set with at least two elements equipped with the so-called chaotic topology

be any set with at least two elements equipped with the so-called chaotic topology ![]() . Then, there is no open

. Then, there is no open ![]() that separates the two distinct elements. Hence, this topology is not a

that separates the two distinct elements. Hence, this topology is not a ![]() -space and definitely also not a Hausdorff space. Hence, it is also not metrizable.

-space and definitely also not a Hausdorff space. Hence, it is also not metrizable.

(b) Let ![]() be any set with the discrete topology

be any set with the discrete topology ![]() . Then,

. Then, ![]() separates the two elements

separates the two elements ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

![]()

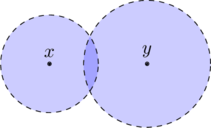

In a ![]() -space two open sets are required to separate two distinct points, however, the two sets don’t need to be disjoint.

-space two open sets are required to separate two distinct points, however, the two sets don’t need to be disjoint.

Definition 2.3. (![]() Space)

Space)

A topological space ![]() is called a

is called a ![]() -space if, for any

-space if, for any ![]() with

with ![]() , there are open sets

, there are open sets ![]() with

with ![]() and

and ![]() and

and ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

![]()

The main difference between a ![]() – and a

– and a ![]() -space is that the two required open sets do not have to be disjoint. However, one open set only contains one of the two distinct points.

-space is that the two required open sets do not have to be disjoint. However, one open set only contains one of the two distinct points.

Hence, every ![]() -space is also a

-space is also a ![]() -space. Just take one of the two open sets of the

-space. Just take one of the two open sets of the ![]() -space and it fulfills all requirements of a

-space and it fulfills all requirements of a ![]() -space.

-space.

Proposition 2.2: (Characterization of ![]() -spaces)

-spaces)

(a) Let ![]() be a topological space. Then,

be a topological space. Then, ![]() is a

is a ![]() -space if and only if

-space if and only if ![]() is a closed set for each

is a closed set for each ![]() ;

;

(b) Each Hausdorff space is a ![]() -space.

-space.

Proof. (a) Suppose ![]() is a

is a ![]() -space, and let

-space, and let ![]() . For any

. For any ![]() with

with ![]() , there is an open subset

, there is an open subset ![]() of

of ![]() with

with ![]() , but

, but ![]() . It follows that

. It follows that ![]() .

.

Conversely, suppose that all singleton subsets of ![]() are closed, and let

are closed, and let ![]() be such that

be such that ![]() . Then,

. Then, ![]() and

and ![]() fulfill the requirements of a

fulfill the requirements of a ![]() -space.

-space.

(b) Let ![]() be a given point. By assumption, each

be a given point. By assumption, each ![]() belongs to an open set

belongs to an open set ![]() such that

such that ![]() . Consequently,

. Consequently, ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() is open, and

is open, and ![]() is closed.

is closed.

![]()

Convergent Sequences

One of the key features of topological spaces is the generalization of the convergence concept.

A sequence in a (metric) space ![]() is a function

is a function ![]() that we also denote by

that we also denote by ![]() , in particular, if we want to refer to the elements of the sequence. Given a sequence

, in particular, if we want to refer to the elements of the sequence. Given a sequence ![]() in a metric space, a sub-sequence is the restriction of

in a metric space, a sub-sequence is the restriction of ![]() to an infinite subset

to an infinite subset ![]() . If we exhibit

. If we exhibit ![]() as

as ![]() , then we write the subsequence

, then we write the subsequence ![]() .

.

We say that a sequence ![]() converges to

converges to ![]() if given

if given ![]() , there exist

, there exist ![]() such that for all

such that for all ![]() , we have

, we have ![]() .

.

In other words, for all ![]() , we have

, we have ![]() as illustrated in Figure above. The finitely many elements

as illustrated in Figure above. The finitely many elements ![]() of the sequence

of the sequence ![]() are, however, not contained in

are, however, not contained in ![]() . We take this property to define what a convergent sequence in a topological space is.

. We take this property to define what a convergent sequence in a topological space is.

Definition 3.1. (Convergent Sequence)

Let ![]() be a topological space. A sequence

be a topological space. A sequence ![]() converges to

converges to ![]() if

if ![]() , the set

, the set ![]() is finite for any open set

is finite for any open set ![]() .

.

The point ![]() is then called the limit of the sequence

is then called the limit of the sequence ![]() and we denote it by

and we denote it by ![]() or by

or by ![]() .

.

![]()

Note that the set of ![]() is infinite for all open sets

is infinite for all open sets ![]() while (at the same time) the set

while (at the same time) the set ![]() is finite. Both sets/conditions matter in this situation as we will see further below!

is finite. Both sets/conditions matter in this situation as we will see further below!

Lemma 3.1. (Limit of a sequence is unique)

The limit ![]() of a convergent sequence

of a convergent sequence ![]() in a Hausdorff space

in a Hausdorff space ![]() is unique.

is unique.

Proof. Assume that this is not the case and ![]() as well as

as well as ![]() with

with ![]() holds true. A metric space is Hausdorff, that is, we find two disjoint open balls

holds true. A metric space is Hausdorff, that is, we find two disjoint open balls ![]() and

and ![]() . Given that

. Given that ![]() and

and ![]() are the limit points almost all elements must lie in the disjoint balls, which contradicts the initial assumption of

are the limit points almost all elements must lie in the disjoint balls, which contradicts the initial assumption of ![]() .

.

![]()

Lemma 1.1 is false in arbitrary topological spaces.

Every ![]() of a topological space

of a topological space ![]() is the limit of a certain sequence

is the limit of a certain sequence ![]() . Apparently, we could simply use the constant sequence

. Apparently, we could simply use the constant sequence ![]() or we could define

or we could define ![]() for all

for all ![]() ,

, ![]() . This fact should be also considered in the following examples.

. This fact should be also considered in the following examples.

Example 3.1:

(a) Let ![]() be the discrete topology with

be the discrete topology with ![]() . Further, let

. Further, let ![]() . Recall that in this topology every set is open by definition. Hence, also

. Recall that in this topology every set is open by definition. Hence, also ![]() is an open set that must be contained in all other (open) supersets. Hence, the set

is an open set that must be contained in all other (open) supersets. Hence, the set ![]() has to be finite and

has to be finite and ![]() has to be infinite.

has to be infinite.

(b) Let ![]() be the indiscrete topology with

be the indiscrete topology with ![]() . Further, let

. Further, let ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is the only set that contains

is the only set that contains ![]() , the set

, the set ![]() has to be finite for every sequence

has to be finite for every sequence ![]() . Hence, every sequence converges to every point in

. Hence, every sequence converges to every point in ![]() .

.

![]()

Closely related to converging sequences and their limits are accumulation points.

Definition 3.2. (Accumulation Point)

An element ![]() of a sequence

of a sequence ![]() is called accumulation point (sometimes also cluster or limit point) if

is called accumulation point (sometimes also cluster or limit point) if ![]() is infinite for every open set

is infinite for every open set ![]() of

of ![]() .

.

![]()

The subtle but important difference between an accumulation point and a limit is that the complement set of ![]() can also be infinite. Let us consider a simple example.

can also be infinite. Let us consider a simple example.

Example 3.2:

Let us consider the sequence ![]() in the topology induced by the Euclidean space

in the topology induced by the Euclidean space ![]() on the real line. There are two accumulation points

on the real line. There are two accumulation points ![]() but no limit of the sequence. Note that the sequence is alternating between

but no limit of the sequence. Note that the sequence is alternating between ![]() and

and ![]() , such that

, such that ![]() and

and ![]() are both infinite but disjoint to each other. In addition, the set

are both infinite but disjoint to each other. In addition, the set ![]() for an open set

for an open set ![]() of

of ![]() are both infinite.

are both infinite.

![]()

A sub-sequence ![]() of a convergent sequence

of a convergent sequence ![]() converges to the same limit

converges to the same limit ![]() . This is evident since if the condition of a convergent sequence is fulfilled for all elements

. This is evident since if the condition of a convergent sequence is fulfilled for all elements ![]() ,

, ![]() of the series

of the series ![]() . Hence, the condition is also fulfilled for a subset

. Hence, the condition is also fulfilled for a subset ![]() that represents the sub-sequence.

that represents the sub-sequence.

Due to the fact that the finiteness of ![]() implies the infiniteness of

implies the infiniteness of ![]() in

in ![]() every limit is an accumulation point. The converse is not true as we can see in Example 3.2.

every limit is an accumulation point. The converse is not true as we can see in Example 3.2.

Theorem 3.1 (Convergence in Topological Spaces)

Let ![]() be a topological space.

be a topological space.

(i) Every limit of a convergent sequence is also the limit of any sub-sequence.

(ii) Every accumulation point of any sub-sequence ![]() is also an accumulation point of

is also an accumulation point of ![]() .

.

(iii) Every accumulation point of a sequence ![]() in

in ![]() is an adherence point of the set

is an adherence point of the set ![]() .

.

Proof. (i) If ![]() then

then ![]() is finite for all open

is finite for all open ![]() of

of ![]() . In particular, this holds true for any sub-sequence

. In particular, this holds true for any sub-sequence ![]() and thus

and thus ![]() .

.

(ii) Let ![]() be an accumulation point of the sub-sequence, i.e. the set

be an accumulation point of the sub-sequence, i.e. the set ![]() is infinite for every open set

is infinite for every open set ![]() of

of ![]() . Since the sub-sequence is only a subset of the element of the sequence, the assertion follows directly.

. Since the sub-sequence is only a subset of the element of the sequence, the assertion follows directly.

(iii) Let ![]() be an accumulation point of

be an accumulation point of ![]() and

and ![]() be an open set of

be an open set of ![]() . Apparently,

. Apparently, ![]() intersects

intersects ![]() since the set

since the set ![]() is infinite. Thus,

is infinite. Thus, ![]() will also intersect

will also intersect ![]() , which implies that

, which implies that ![]() Cl

Cl![]() .

.

![]()

Let us now assume that ![]() and

and ![]() is a converging sequence with

is a converging sequence with ![]() for all

for all ![]() . Then, the limit point

. Then, the limit point ![]() is also contained in

is also contained in ![]() . A closed set contains all its limit points.

. A closed set contains all its limit points.

Compactness

The concept of compactness is not as intuitive as others topics such as continuity. In ![]() , the compact sets are the closed and bounded sets, but in a general topology compact sets are not as simple to describe.

, the compact sets are the closed and bounded sets, but in a general topology compact sets are not as simple to describe.

Compact sets are so important since they possess important properties, that are known from finite sets:

- Set is bounded;

- Set contains a maximal and minimal element;

- An infinite sequence contains a constant subsequence.

The famous Heine-Borel Theorem shows that compact sets in metric spaces do indeed have these properties. This analogy is also outlined in this really nice video (in German only) by Prof. Dr. Edmund Weitz.

Let ![]() be a topological space.

be a topological space.

Definition 4.1 (Cover)

The collection ![]() is said to cover a set

is said to cover a set ![]() or to be a cover of

or to be a cover of ![]() if the union of the elements of

if the union of the elements of ![]() contains

contains ![]() .

.

If ![]() covers

covers ![]() , and each set in

, and each set in ![]() is open, then we call

is open, then we call ![]() an open cover of

an open cover of ![]() .

.

A sub-collection ![]() of a cover is called a subcover of

of a cover is called a subcover of ![]() .

.

![]()

A cover of ![]() is a collection of possibly overlapping sets in

is a collection of possibly overlapping sets in ![]() which, after considering their union globally, contains the set

which, after considering their union globally, contains the set ![]() inside.

inside.

Example 4.1 (Real Line)

Let us consider the set ![]() of the topological space

of the topological space ![]() , where

, where ![]() are the open sets of

are the open sets of ![]() . Note that any nonempty open subset of

. Note that any nonempty open subset of ![]() can be written as a finite or countable union of open mutually disjoint intervals.

can be written as a finite or countable union of open mutually disjoint intervals.

Then, ![]() is an open cover of

is an open cover of ![]() because

because ![]() . This cover apparently contains infinitely many open sets

. This cover apparently contains infinitely many open sets ![]() .

.

![]() is an open subcover of

is an open subcover of ![]() since

since ![]() and

and ![]() . This subcover, however, still contains infinitely many open sets.

. This subcover, however, still contains infinitely many open sets.

![]()

Now, we have the ingredients for the central definition of this section.

Definition 4.2 (Compact Set)

A subset ![]() of a topological space

of a topological space ![]() is said to be compact if every open cover

is said to be compact if every open cover ![]() of

of ![]() has a finite (open) subcover.

has a finite (open) subcover.

A topological space ![]() is called compact if

is called compact if ![]() is compact.

is compact.

![]()

It is clear that every finite set is compact and the following example is going to illustrate that.

Example 4.2 (Finite Set & Compactness)

Let ![]() be a finite set in the standard Euclidean topological space

be a finite set in the standard Euclidean topological space ![]() . By setting

. By setting

![]()

with ![]() , an open set

, an open set ![]() is assigned bijectively to each point

is assigned bijectively to each point ![]() . Hence, the set

. Hence, the set ![]() is an open and finite cover for any set

is an open and finite cover for any set ![]() . Each point of the finite set

. Each point of the finite set ![]() is contained in one of the elements of

is contained in one of the elements of ![]() . Given any open cover

. Given any open cover ![]() , we can always use

, we can always use ![]() with

with ![]() small enough simply because there are only finitely many elements in

small enough simply because there are only finitely many elements in ![]() .

.

![]()

Let us consider another simple example.

Example 4.3 (Real Line)

The real line ![]() in the standard Euclidean topology is not compact since the set

in the standard Euclidean topology is not compact since the set ![]() of Example 5.1 is an open cover, but no finite sub-collection of

of Example 5.1 is an open cover, but no finite sub-collection of ![]() covers

covers ![]() . If we picked finitely many open sets of

. If we picked finitely many open sets of ![]() the points before the minimum / after the maximum of this sub-collection would not be covered.

the points before the minimum / after the maximum of this sub-collection would not be covered.

![]()

The last example directly used the definition of a compact set to show that it is not compact since every open cover needs to have a finite sub-cover such that the set can be compact.

Even though ![]() is a finite open cover of

is a finite open cover of ![]() , this does not mean that

, this does not mean that ![]() is compact: if it were compact, all open covers (including the one defined in Example 5.2/5.3) would have to have a finite sub-cover.

is compact: if it were compact, all open covers (including the one defined in Example 5.2/5.3) would have to have a finite sub-cover.

Example 4.4 (Converging Sequence & Compact Set)

(a) The subset ![]()

![]() is compact in the standard topology on

is compact in the standard topology on ![]() .

.

Given any open cover ![]() of

of ![]() , there is an element set

, there is an element set ![]() containing

containing ![]() . The set

. The set ![]() contains either all points or all but finitely many of

contains either all points or all but finitely many of ![]() . If

. If ![]() contains all of the points in

contains all of the points in ![]() , then

, then ![]() , by itself, is a finite subcover of

, by itself, is a finite subcover of ![]() . Otherwise, let

. Otherwise, let ![]() be the smallest of the points in

be the smallest of the points in ![]() that are not in

that are not in ![]() . Then we can pick open sets

. Then we can pick open sets ![]() for

for ![]() ,

, ![]() for

for ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() for

for ![]() such that

such that ![]() is a finite sub-cover of

is a finite sub-cover of ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() is compact.

is compact.

(b) The compact sets of the discrete topology ![]() are finite. To see this realize that all subsets of

are finite. To see this realize that all subsets of ![]() are open and closed. Thus, all possible families of subsets can be open covers. For instance, the family

are open and closed. Thus, all possible families of subsets can be open covers. For instance, the family ![]() is an open cover and if

is an open cover and if ![]() is of infinite cardinality, so is

is of infinite cardinality, so is ![]() . If we leave out one of the elements of

. If we leave out one of the elements of ![]() it would not be a cover. Hence, there can be no open subcover, which implies that the compact sets are finite. Refer also to this formal proof.

it would not be a cover. Hence, there can be no open subcover, which implies that the compact sets are finite. Refer also to this formal proof.

![]()

Let us now extend the definition of compactness to subsets of topological spaces.

Definition 4.1 (Subspace Topology)

Let ![]() be a topological space. If

be a topological space. If ![]() , the collection

, the collection

![]()

is a topology on ![]() , called the subspace topology. With this topology,

, called the subspace topology. With this topology, ![]() is called topological subspace of

is called topological subspace of ![]() .

.

![]()

Let us check that ![]() is indeed a topology. It contains

is indeed a topology. It contains ![]() and

and ![]() because

because ![]() and

and ![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() on the right-hand side of the

on the right-hand side of the ![]() -symbol are elements of

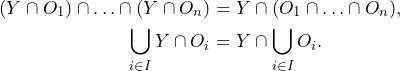

-symbol are elements of ![]() . The fact that it is closed under finite intersections and arbitrary unions follows from the equations

. The fact that it is closed under finite intersections and arbitrary unions follows from the equations

Lemma 4.1 (Compactness & Subspaces)

Let ![]() be a subspace of

be a subspace of ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() is compact in

is compact in ![]() if and only if every open cover of

if and only if every open cover of ![]() by open sets in

by open sets in ![]() contains a finite subcover of

contains a finite subcover of ![]() .

.

Proof. Suppose that ![]() is compact and

is compact and ![]() is a cover of

is a cover of ![]() by sets open in

by sets open in ![]() . Then the collection

. Then the collection ![]() is a covering of

is a covering of ![]() by sets open in

by sets open in ![]() . Due to the assumption that

. Due to the assumption that ![]() is compact in

is compact in ![]() , there exists a finite subcover

, there exists a finite subcover

![]()

in ![]() . For each

. For each ![]() chose a set

chose a set ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

covers ![]() .

.

Suppose that every open cover of ![]() by sets open in

by sets open in ![]() contains a finite open subcover of

contains a finite open subcover of ![]() . We would like to show that

. We would like to show that ![]() is compact in

is compact in ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be an open cover of

be an open cover of ![]() by sets open in

by sets open in ![]() (and thus in

(and thus in ![]() ). By hypothesis, some finite subcollection

). By hypothesis, some finite subcollection ![]() exists that covers

exists that covers ![]() . Then, by definition of the subspace topology, for each

. Then, by definition of the subspace topology, for each ![]() ,

, ![]() we can chose an open set

we can chose an open set ![]() via

via ![]() . It follows that

. It follows that ![]() is a finite subcover of

is a finite subcover of ![]() in

in ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() is compact in

is compact in ![]() .

.

![]()

A closed subspace is a subspace ![]() , that when treated as a subset of the original space

, that when treated as a subset of the original space ![]() is a closed set in the original topology

is a closed set in the original topology ![]() .

.

Theorem 4.1 (Compactness & Closed Spaces)

Every closed subspace ![]() of a compact space

of a compact space ![]() is compact.

is compact.

Proof. Let ![]() be a closed subspace of the compact space

be a closed subspace of the compact space ![]() . Given a covering

. Given a covering ![]() of

of ![]() by sets open in

by sets open in ![]() , let us form an open cover

, let us form an open cover ![]() by adjoining to

by adjoining to ![]() the single open set

the single open set ![]() . Note that

. Note that ![]() is closed such that its complement needs to be open.

is closed such that its complement needs to be open.

Thus, ![]() is an open cover of

is an open cover of ![]() . Due to the fact that

. Due to the fact that ![]() is compact, some finite subcollection of

is compact, some finite subcollection of ![]() covers

covers ![]() . If this subcollection contains the set

. If this subcollection contains the set ![]() , discard

, discard ![]() . Otherwise, leave the subcollection alone. The resulting collection is a finite cover of

. Otherwise, leave the subcollection alone. The resulting collection is a finite cover of ![]() that covers

that covers ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() is compact.

is compact.

![]()

Theorem 4.2 (Compactness in Hausdorff Spaces)

Every compact subspace ![]() of a Hausdorff space

of a Hausdorff space ![]() is closed.

is closed.

Proof. Let ![]() be a compact subspace of a Hausdorff space

be a compact subspace of a Hausdorff space ![]() . We are going to prove that

. We are going to prove that ![]() is open, so that

is open, so that ![]() is closed.

is closed.

Let ![]() . We show there is a neighborhood of

. We show there is a neighborhood of ![]() that is disjoint from

that is disjoint from ![]() . For each point

. For each point ![]() , let us choose disjoint neighborhoods

, let us choose disjoint neighborhoods ![]() and

and ![]() of the points

of the points ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively (using the Hausdorff condition). The collection

, respectively (using the Hausdorff condition). The collection ![]() is a covering of

is a covering of ![]() by sets open in

by sets open in ![]() . Therefore, finitely many of them

. Therefore, finitely many of them ![]() cover

cover ![]() (since

(since ![]() is assumed to be compact). The open set

is assumed to be compact). The open set ![]() contains

contains ![]() . The open set

. The open set ![]() contains all points that are disjoint from any of the open sets

contains all points that are disjoint from any of the open sets ![]() and thus

and thus ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() is a neighborhood of some arbitrary

is a neighborhood of some arbitrary ![]() and thus

and thus ![]() is closed.

is closed.

![]()

Example 4.5 (Theorems 4.1 and 4.2)

(a) Once we prove that the interval ![]() in

in ![]() is compact, it follows from Theorem 4.1 that any closed subspace of

is compact, it follows from Theorem 4.1 that any closed subspace of ![]() is compact. On the other hand, it follows from Theorem 4.2 that the intervals

is compact. On the other hand, it follows from Theorem 4.2 that the intervals ![]() and

and ![]() in

in ![]() cannot be compact because they are not closed in the Hausdorff space

cannot be compact because they are not closed in the Hausdorff space ![]() .

.

(b) The Hausdorff condition in Theorem 4.2 is necessary. Consider the finite complement topology on the real line. The only proper subsets of ![]() that are closed in this topology are the finite sets. But every subset of

that are closed in this topology are the finite sets. But every subset of ![]() is compact in this topology since you can always find an open finite subcover given any open cover.

is compact in this topology since you can always find an open finite subcover given any open cover.

(c) The interval ![]() is not compact in the Euclidean standard topology of

is not compact in the Euclidean standard topology of ![]() . The open cover

. The open cover ![]() contains no finite sub-collection covering

contains no finite sub-collection covering ![]() .

.

![]()

Continuous Functions

Topological spaces have been introduced because they are the natural habitat for continuous functions. These spaces have been built such that the topological structure is respected. Continuous functions therefore take the same role on topological spaces as linear maps within vector spaces.

The notion of continuity is particularly easy to formulate in terms of open (and closed) sets and the following version is called the open set definition of continuity.

Definition 5.1: (Continuous Function on Topological Space)

Let ![]() and

and ![]() be two topological spaces. A function

be two topological spaces. A function ![]() is continuous if

is continuous if ![]() is open in

is open in ![]() for every open set

for every open set ![]() in

in ![]() .

.

![]()

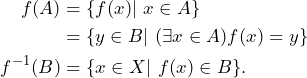

Before we will illustrate this definition let us recall the definitions of an image ![]() and a preimage

and a preimage ![]() of a function

of a function ![]() with

with ![]() ,

, ![]() :

:

The condition that ![]() be continuous says that for each open set

be continuous says that for each open set ![]() of

of ![]() , the inverse image of

, the inverse image of ![]() under the map

under the map ![]() is open in

is open in ![]()

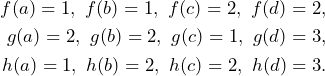

Example 5.1: (Simple Continuous Function)

Let ![]() and

and ![]() be two topological spaces defined by

be two topological spaces defined by

![]()

Let ![]() be three functions defined by

be three functions defined by

The functions ![]() is continuous since the pre-image of each open set in

is continuous since the pre-image of each open set in ![]() is an element of

is an element of ![]() . Similarly,

. Similarly, ![]() is continuous but note that

is continuous but note that ![]() is not an open set. The function

is not an open set. The function ![]() , however, is not continuous since

, however, is not continuous since ![]() is open in

is open in ![]() , but

, but ![]() is not open in

is not open in ![]() .

.

Let us now study how the functions map closed sets. By definitions these are the complements of ![]() and

and ![]() , i.e.

, i.e.

Recognize that the image of a closed set in ![]() under

under ![]() and

and ![]() is contained in a closed set in

is contained in a closed set in ![]() . For instance,

. For instance, ![]()

![]()

![]() and

and ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

![]()

The last example made the definition of a continuous function between simple topological spaces rather clear.

Sometimes it is also helpful to study the properties that will not be preserved: a continuous function does not necessarily map open sets to open sets.

For example, the function ![]() , given by

, given by ![]() , is continuous, but the image of the open set

, is continuous, but the image of the open set ![]() is

is ![]() , which is neither open nor closed. Let us also double-check that in Example 4.1. The function

, which is neither open nor closed. Let us also double-check that in Example 4.1. The function ![]() maps the open set

maps the open set ![]() to

to ![]() , which is not open.

, which is not open.

Now, let us have a look at more general examples.

Example 5.2: (Identity and Constant Function)

(a) The identity function id:![]() , given by id

, given by id![]() , is continuous in all topological spaces. If a function

, is continuous in all topological spaces. If a function ![]() is continuous at

is continuous at ![]() , i.e. if

, i.e. if ![]() is open so is its preimage

is open so is its preimage ![]() . This argument can be generalized onto subsets

. This argument can be generalized onto subsets ![]() .

.

(b) The constant function ![]() defined by

defined by ![]() for every

for every ![]() . Suppose

. Suppose ![]() is open in

is open in ![]() , then

, then ![]() if

if ![]() , and

, and ![]() if

if ![]() . In either case, the preimage is open in

. In either case, the preimage is open in ![]() , and therefore

, and therefore ![]() is continuous.

is continuous.

![]()

Continuous functions preserve proximity as we can see in the next theorem. Also refer to Example 4.1.

Theorem 5.1 (Continuous Functions & Closeness)

Let ![]() be continuous and assume that

be continuous and assume that ![]() . If

. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() .

.

Proof. Suppose that ![]() is continuous,

is continuous, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . We prove that if

. We prove that if ![]() , then

, then ![]() .

.

Hence, suppose that ![]() . By Proposition 1.2 there exists an open set

. By Proposition 1.2 there exists an open set ![]() containing

containing ![]() , but not intersecting

, but not intersecting ![]() . It follows that

. It follows that ![]() is an open set containing

is an open set containing ![]() that does not intersect

that does not intersect ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() , and the result follows.

, and the result follows.

![]()

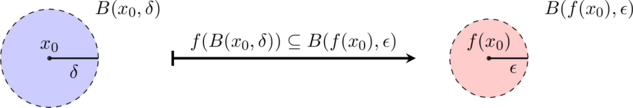

The next theorem translates the well-known ![]() –

–![]() definition of continuity with Definition 4.1.

definition of continuity with Definition 4.1.

Theorem 5.2 (Continuity & ![]() –

–![]() Condition)

Condition)

A function ![]() is continuous in the open set definition of continuity if and only if, for every

is continuous in the open set definition of continuity if and only if, for every ![]() and every open set

and every open set ![]() containing

containing ![]() , there exists a neighborhood

, there exists a neighborhood ![]() of

of ![]() such that

such that ![]() .

.

Proof. First, suppose that the open set definition holds for functions ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() and an open set

and an open set ![]() containing

containing ![]() be given. Set

be given. Set ![]() . It follows that

. It follows that ![]() and that

and that ![]() is open in

is open in ![]() since

since ![]() is continuous by the open set definition 4.1. Clearly,

is continuous by the open set definition 4.1. Clearly, ![]() , and therefore we have shown the desired result.

, and therefore we have shown the desired result.

Now assume that for every ![]() and every open set

and every open set ![]() containing

containing ![]() , there exist a neighborhood

, there exist a neighborhood ![]() of

of ![]() such that

such that ![]() . We show that

. We show that ![]() is open in

is open in ![]() for every open set

for every open set ![]() in

in ![]() . Hence, let

. Hence, let ![]() be an arbitrary open set in

be an arbitrary open set in ![]() . To show that

. To show that ![]() is open in

is open in ![]() , choose an arbitrary

, choose an arbitrary ![]() . It follows that

. It follows that ![]() , and therefore exists a neighborhood

, and therefore exists a neighborhood ![]() of

of ![]() in

in ![]() such that

such that ![]() , or, equivalently, such that

, or, equivalently, such that ![]() . Thus, for an arbitrary

. Thus, for an arbitrary ![]() there exists an open set

there exists an open set ![]() such that

such that ![]() . Then, the assertion follows applying Theorem 1.1.

. Then, the assertion follows applying Theorem 1.1.

![]()

Theorem 4.2 generalizes this idea of continuity in metrizable topological spaces to general topological spaces. In a metric space, we can consider an open ball as an open set and therefore as a neighborhood. That is, for each ![]() -ball

-ball ![]() there need to be a suitable

there need to be a suitable ![]() -ball

-ball ![]() , such that

, such that ![]() . For further details please refer to this deep-mind.org post and this Wikipedia article.

. For further details please refer to this deep-mind.org post and this Wikipedia article.

The second important property that is preserved by continuous functions is the concept of convergence.

Theorem 5.3 (Continuity & Convergent Sequences)

Assume that ![]() is continuous. If a sequence

is continuous. If a sequence ![]() in

in ![]() converges to a point

converges to a point ![]() , then the sequence

, then the sequence ![]() in

in ![]() converges to

converges to ![]() .

.

Proof. Let ![]() be an arbitrary neighborhood of

be an arbitrary neighborhood of ![]() in

in ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is continuous,

is continuous, ![]() is open in

is open in ![]() . Furthermore,

. Furthermore, ![]() implies that

implies that ![]() . The sequence

. The sequence ![]() converges to

converges to ![]() ; thus, there exists

; thus, there exists ![]() such that

such that ![]() for all

for all ![]() . It follows that

. It follows that ![]() for all

for all ![]() , and therefore the sequence

, and therefore the sequence ![]() converges to

converges to ![]() .

.

![]()

Another important property of continuous functions is directly linked to the actual definition.

Theorem 5.4 (Continuity & Pre-Image of Closed Sets)

Let ![]() and

and ![]() be topological spaces. A function

be topological spaces. A function ![]() is continuous if and only if

is continuous if and only if ![]() is closed in

is closed in ![]() for every closed set

for every closed set ![]() .

.

Proof. Let ![]() be closed in

be closed in ![]() and let

and let ![]() . We wish to prove that

. We wish to prove that ![]() is closed in

is closed in ![]() . We show that Cl

. We show that Cl![]() . By elementary set theory, we have

. By elementary set theory, we have ![]() . Therefore, if

. Therefore, if ![]() then

then ![]()

![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() and Cl

and Cl![]() and thus Cl

and thus Cl![]() .

.

![]()

Theorem 5.5 (Continuous Functions & Compact Sets)

Let ![]() be continuous, and let

be continuous, and let ![]() be compact in

be compact in ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() is compact in

is compact in ![]() .

.

Proof. Let ![]() be continuous, and assume that

be continuous, and assume that ![]() is compact in

is compact in ![]() . To show that

. To show that ![]() is compact in

is compact in ![]() , let

, let ![]() be a cover of

be a cover of ![]() by open sets in

by open sets in ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() is open in

is open in ![]() for every set

for every set ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() is a cover of

is a cover of ![]() by open sets in

by open sets in ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is compact there is a finite sub-collection of

is compact there is a finite sub-collection of ![]() that covers

that covers ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() has a finite sub-cover, implying that

has a finite sub-cover, implying that ![]() is compact in

is compact in ![]() .

.

![]()

Appendix

A really nice introduction to the abstract concept of a topology, however, in German language only.

Literature

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]