Contents

Introduction

Copulas are an important concept in statistics and beyond to describe dependency structures of continuous distributions. However, what can we do if we have multivariate data at hand. And how can we do that?

The following blog post provides a hands-on approach to empirical copulas. It provides insight and illustrations.

Let us assume we have a sample of two random variables ![]() and

and ![]() at hand, and we would like to know more about how both variables are interrelated to each other. The elements of the sample of size

at hand, and we would like to know more about how both variables are interrelated to each other. The elements of the sample of size ![]() of both random variables shall be denoted as a tuple

of both random variables shall be denoted as a tuple ![]() with

with ![]() .

.

The empirical (bivariate) copula is defined as the discrete function ![]() given by

given by

(1) ![]()

where ![]() and

and ![]() ,

, ![]() denote the order statistics of the sample and

denote the order statistics of the sample and ![]() provides the cardinality of the subsequent set. For instance,

provides the cardinality of the subsequent set. For instance, ![]() .

.

Notice that the definition is actually a special case of the definition of an empirical distribution function. However, empirical copula functions are only defined on ![]() and they represent a dependency structure and not a distribution.

and they represent a dependency structure and not a distribution.

Hands-on Approach

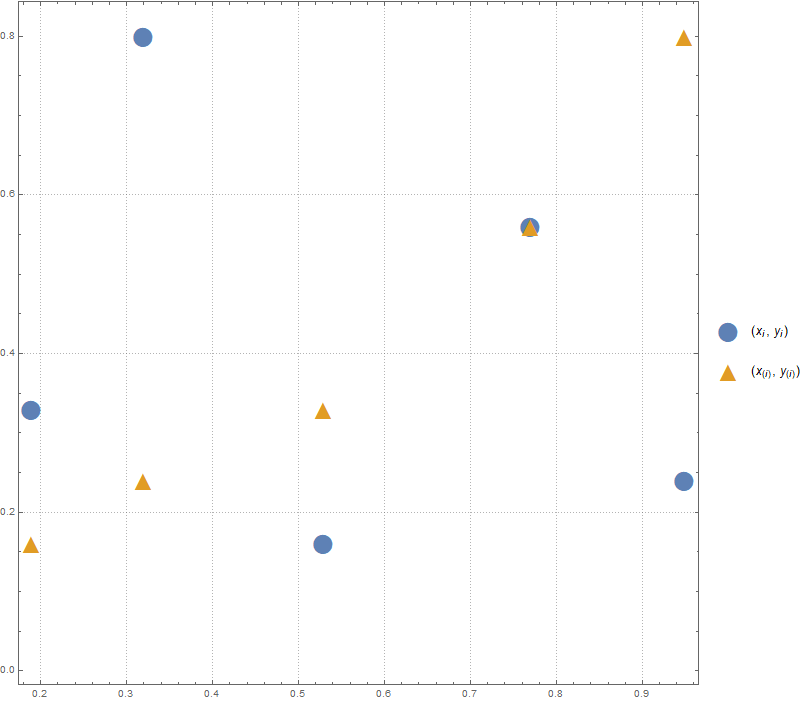

Uniformly with a sample size of n=5

First, let us assume that ![]() and

and ![]() follow an uniform distribution on

follow an uniform distribution on ![]() . For both random variables we draw a small sample of size

. For both random variables we draw a small sample of size ![]() . The sample is listed in the following table and illustrated in the plot below (blue points).

. The sample is listed in the following table and illustrated in the plot below (blue points).

| 1 | 0.95 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.16 |

| 2 | 0.53 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.24 |

| 3 | 0.77 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.33 |

| 4 | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.77 | 0.56 |

| 5 | 0.32 | 0.80 | 0.95 | 0.80 |

According to the definition of the empirical copula, we also need to know the corresponding ordered samples ![]() and

and ![]() , which can also be found in the table above. In addition, the tuples of the order statistic

, which can also be found in the table above. In addition, the tuples of the order statistic ![]() are also sketched in the plot below (orange triangles).

are also sketched in the plot below (orange triangles).

as well as of the order statistic

as well as of the order statistic

The domain of the empirical copula is the Cartesian product of the values ![]() . For instance,

. For instance, ![]() since no tupel

since no tupel ![]() exists such that

exists such that ![]() and

and ![]() for

for ![]() . However, for

. However, for ![]() and

and ![]() the tuple

the tuple ![]() meet the conditions

meet the conditions ![]() and

and ![]() with

with ![]() .

.

By knowing the set in the numerator of equation (1), we are able to derive the corresponding empirical copula value easily. We just need to count the elements of this set and divide the number by the sample size ![]() . The result is the desired empirical copula value which is a (cumulative) frequency.

. The result is the desired empirical copula value which is a (cumulative) frequency.

Note that the set of equation (1) corresponds to all points ![]() that lie within the rectangles intersecting the

that lie within the rectangles intersecting the ![]() and

and ![]() axes, respectively, passing through

axes, respectively, passing through ![]() .

.

The values ![]() are listed in the following table.

are listed in the following table.

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | |

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.40 | |

| 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.60 | |

| 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.80 | |

| 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.80 | 1.00 |

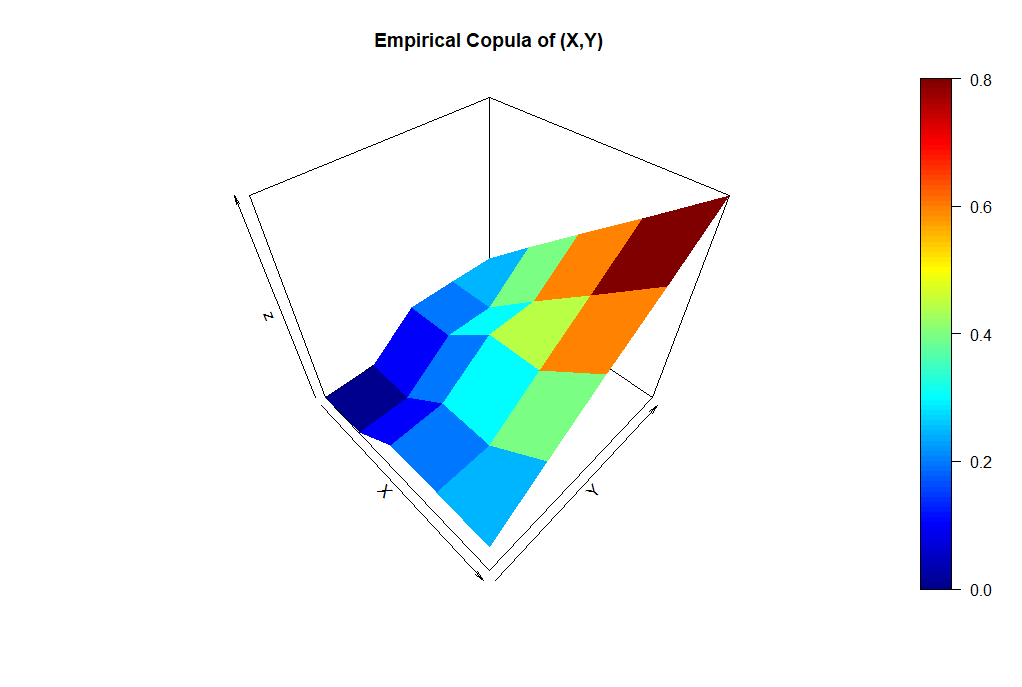

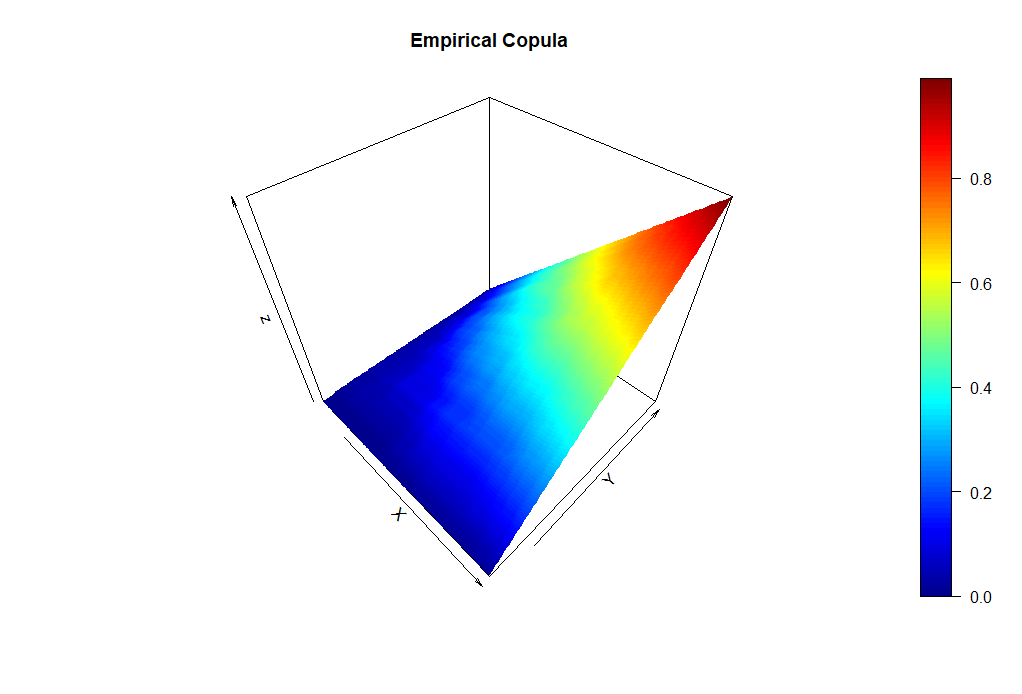

Graphically the empirical copula looks as follows:

where both variables are distributed uniformly on

where both variables are distributed uniformly on ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com [0,1]](https://www.deep-mind.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-0621f04d8a0d9e76a5abce6204d5b435_l3.png)

Normally distributed with a sample size of n=100

Second, let us now assume that ![]() follows a bivariate normal distributed with mean

follows a bivariate normal distributed with mean ![]() and

and

![]()

.

Here, ![]() is the correlation coefficient between

is the correlation coefficient between ![]() and

and ![]() . We draw a bivariate sample of size

. We draw a bivariate sample of size ![]() with

with ![]() using R.

using R.

library(mvtnorm) #package to simulate joint normal distribution

n <- 100 #sample size

# parameters of the bivariate normal

mean <- c(0,0) # mean for distribution

sigma <- matrix(c(1,0.3,0.3,1), ncol=2) # correlation matrix

# sample the bivariate normal

Z <- rmvnorm(n=n, mean = mean, sigma = sigma) # simulate bivariate normally distributed sample

plot(Z, main="Bivariate Normal, Correlation 0.3, X vs. Y")

# divide Z to get X and Y

X <- Z[,1]

Y <- Z[,2]

# sort sample

X.ascending <- sort(X)

Y.ascending <- sort(Y)

Z.ascending <- cbind(X.ascending, Y.ascending)

# prepare data structure

C.n <- as.data.frame(matrix(nrow = n, ncol = n), row.names = paste0("X", 1:n))

colnames(C.n) <- paste0("Y", 1:n)

# run through the indizes i (of X) and j (of Y)

for( i in 1:n){

for( j in 1:n){

C.n[i, j] <- sum(apply(X=Z, MARGIN = 1, FUN = function(Z.row, x.sorted, y.sorted) { sum(Z.row <= c(x.sorted, y.sorted), na.rm = TRUE) >=2 }, X.ascending[i], Y.ascending[j]), na.rm = TRUE)/n

}

}

# plot the empirical copula

library(plot3D)

x <- (1:n)/n

y <- x

persp3D(x = x, y = y, z = as.matrix(C.n), phi = 45, theta = 45, xlab = "X", ylab = "Y", main = "Empirical Copula")

We basically apply the same algorithm to calculate the empirical copula values, which are computed within the loops and named by C.n[i, j]. The arguments i and j represent the values of the domain of the empirical copula. The defined function then just counts whether what conditions are met and divides by ![]() .

.

The plot created by R (for my specific random variate) can be seen in the following.

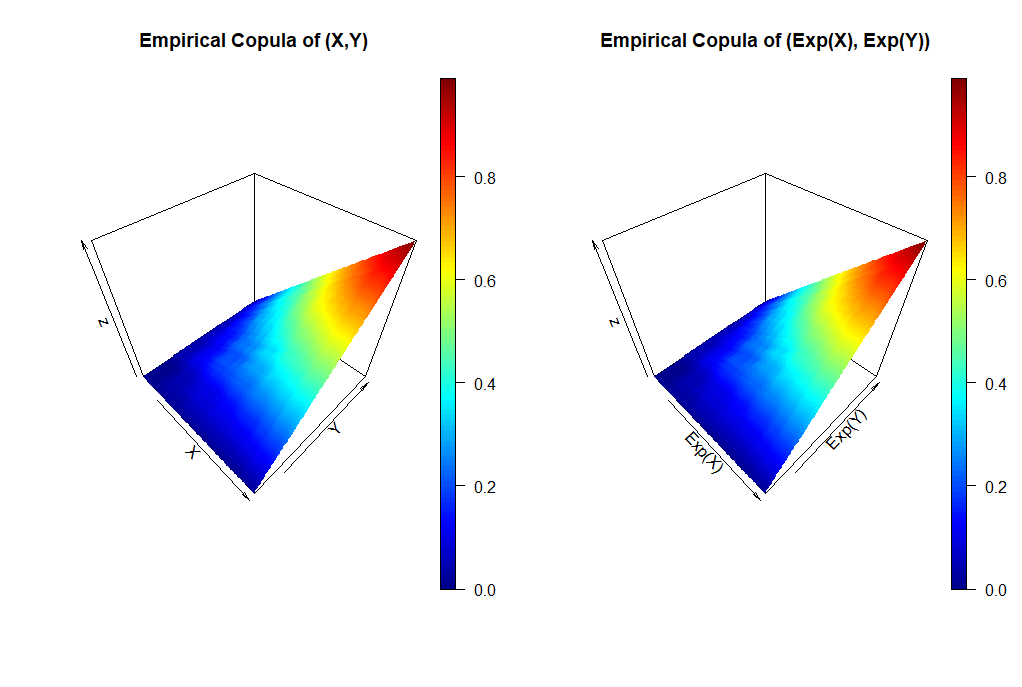

Transforming the normally distributed sample

Let us further use the random sample ![]() with

with ![]() that we have just simulated. However, let us define new random variables

that we have just simulated. However, let us define new random variables ![]() and

and ![]() by transforming the samples

by transforming the samples ![]() ,

, ![]() with

with ![]() accordingly.

accordingly.

What do you think how the corresponding empirical copula will look like?

Well, given that ![]() is a monotone function nothing will change since the order of the sample will not change. The following R code demonstrates that.

is a monotone function nothing will change since the order of the sample will not change. The following R code demonstrates that.

library(mvtnorm) #package to simulate joint normal distribution

library(mvtnorm) #package to simulate joint normal distribution

n <- 100 #sample size

# parameters of the bivariate normal

mean <- c(0,0) # mean for distribution

sigma <- matrix(c(1,0.3,0.3,1), ncol=2) # correlation matrix

# sample the bivariate normal

Z <- rmvnorm(n=n, mean = mean, sigma = sigma) # simulate bivariate normally distributed sample

plot(Z, main="Bivariate Normal, Correlation 0.3, X vs. Y")

# divide Z to get X and Y

X <- Z[,1]

Y <- Z[,2]

cor(X,Y)

# apply a monotone transformation to X and Y

R <- exp(X)

S <- exp(Y)

cor(R, S)

T <- cbind(R, S)

# sort simulated sample

X.ascending <- sort(X)

Y.ascending <- sort(Y)

Z.ascending <- cbind(X.ascending, Y.ascending)

# sort transformed sample

R.ascending <- sort(R)

S.ascending <- sort(S)

T.ascending <- cbind(R.ascending, S.ascending)

# prepare data structures

C.n <- as.data.frame(matrix(nrow = n, ncol = n), row.names = paste0("X", 1:n))

colnames(C.n) <- paste0("Y", 1:n)

C.n.trans <- as.data.frame(matrix(nrow = n, ncol = n), row.names = paste0("R", 1:n))

colnames(C.n.trans) <- paste0("S", 1:n)

# run through the indizes i (of X/R) and j (of Y/S)

for( i in 1:n){

for( j in 1:n){

C.n[i, j] <- sum(apply(X=Z, MARGIN = 1, FUN = function(Z.row, x.sorted, y.sorted) { sum(Z.row <= c(x.sorted, y.sorted), na.rm = TRUE) >=2 }, X.ascending[i], Y.ascending[j]), na.rm = TRUE)/n

C.n.trans[i, j] <- sum(apply(X=T, MARGIN = 1, FUN = function(T.row, r.sorted, s.sorted) { sum(T.row <= c(r.sorted, s.sorted), na.rm = TRUE) >=2 }, R.ascending[i], S.ascending[j]), na.rm = TRUE)/n

}

}

# plot the empirical copula

library(plot3D)

x <- (1:n)/n

y <- x

par(mfrow=c(1, 2)); #prepare canvas

persp3D(x = x, y = y, z = as.matrix(C.n), phi = 45, theta = 45, xlab = "X", ylab = "Y", main = "Empirical Copula of (X,Y)")

persp3D(x = x, y = y, z = as.matrix(C.n.trans), phi = 45, theta = 45, xlab = "Exp(X)", ylab = "Exp(Y)", main = "Empirical Copula of (Exp(X), Exp(Y))")

and transformed

and transformed

The comparison of both plots show graphically that the empirical copula does not change by the transformation.

For all who would like to know more about empirical copulas I recommend [1] by Genest et al.