Introduction

Vector spaces are one of the most fundamental and important algebraic structures that are used far beyond math and physics. This algebraic structure has appeared in many real world problems and is therefore known for centuries.

In this post, we study specific vector spaces where the vectors are not tuples but functions. This raises several challenges since general function spaces are infinite dimensional and concepts like basis and linear independence might be reconsidered. We will, however, focus on mechanics of a function space without diving too deep into the realm of infinite dimensional vector spaces and its specifics.

The branch of math that studies function spaces is called functional analysis. For those who have no exposure to functional analysis, the introduction series to functional analysis provided by The Bright Side of Mathematics on YouTube or one of the book from the literature might help to get you up to speed.

Recap of Vector Spaces

Let us start with the two pivotal definitions of this post.

Definition 1.1 (Vector Space)

Let ![]() be a field. A

be a field. A ![]() vector space is a set

vector space is a set ![]() of vectors along with an operation

of vectors along with an operation

![]()

and a function, called scalar multiplication,

![]()

such that the following axioms are fulfilled.

(i) Addition: ![]() is an Abelian group. That is,

is an Abelian group. That is,

(a) ![]() for all

for all ![]()

(b) ![]() such that

such that ![]() for all

for all ![]()

(c) ![]()

![]() such that

such that ![]()

(d) ![]()

![]()

(ii) Compatibility of scalar multiplication with field multiplication: ![]() for all

for all ![]() and all

and all ![]() .

.

(iii) Distributive property:![]() and

and![]() for all

for all ![]() and all

and all ![]() .

.

The elements of ![]() are called scalars and the elements of

are called scalars and the elements of ![]() are called vectors.

are called vectors.

![]()

Every vector space consists of a field ![]() and an Abelian group

and an Abelian group ![]() . These two mathematical structures are entangled with each other via (ii) and (iii).

. These two mathematical structures are entangled with each other via (ii) and (iii).

There are two additions defined. One addition for the scalar field ![]() and another for the set of vectors

and another for the set of vectors ![]() . Therefore, there are also two corresponding null elements defined – the null vector and the null element of the field. We nonetheless use for both additions the same symbol

. Therefore, there are also two corresponding null elements defined – the null vector and the null element of the field. We nonetheless use for both additions the same symbol ![]() since it is obvious to see, which one is meant. A similar treatment is applied to similar situations. For instance, there is little danger that the zero scalar can be confused with the zero vector, so no attempt is made to distinguish them.

since it is obvious to see, which one is meant. A similar treatment is applied to similar situations. For instance, there is little danger that the zero scalar can be confused with the zero vector, so no attempt is made to distinguish them.

Let us first consider classical vector space examples before diving in to function spaces.

Example 1.1 (Real finite-dimensional vector space ![]() )

)

Let ![]() ,

, ![]() the tuples with real entries and

the tuples with real entries and ![]() . For

. For ![]() as well as

as well as ![]() with

with ![]() and

and ![]() , let us define the addition and scalar multiplication as follows.

, let us define the addition and scalar multiplication as follows.

![]()

The axioms follow almost immediately by the properties of ![]() due to the definition of the addition of vectors and the scalar multiplication. The additive inverse of a vector

due to the definition of the addition of vectors and the scalar multiplication. The additive inverse of a vector ![]() is simply

is simply ![]() since

since ![]() . The null vector is

. The null vector is ![]() , for example.

, for example.

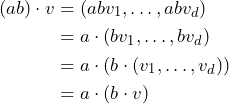

Requirements (ii) and (iii) can also be shown by using the properties of ![]() and the definition of the operation and the scalar multiplication. Let us prove (ii)

and the definition of the operation and the scalar multiplication. Let us prove (ii) ![]() , for instance. By definition the following holds true:

, for instance. By definition the following holds true:

for all ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

![]()

The last example is the raw model for the imagination of finite-dimensional vector spaces. The focus of this post is, however, on function spaces and their algebraic structure. We are particularly interested in function spaces that are (infinite dimensional) vector spaces.

Functions are employed everywhere in mathematics. Let us also recap its definition.

Definition 1.1 (Function)

A function from a set X to a set Y is an assignment of an element of Y to each element of X. The set X is called the domain of the function and the set Y is called the codomain or range of the function.

![]()

The important feature of a function is, that every element of ![]() needs to be assigned to an element of

needs to be assigned to an element of ![]() .

.

Example 1.2: (Homorphism Function Space)

If ![]() is a vector space, then so is the set of functions

is a vector space, then so is the set of functions ![]() for any set

for any set ![]() with

with

![]()

The zero of ![]() is

is ![]() , and the negatives are

, and the negatives are ![]() . The addition of two functions

. The addition of two functions ![]() is defined by

is defined by ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() and

and ![]() are two vectors in

are two vectors in ![]() , the sum also needs to be a vector in

, the sum also needs to be a vector in ![]() . Hence, by using the properties of the given objects it is not too hard to show that the given set

. Hence, by using the properties of the given objects it is not too hard to show that the given set ![]() is indeed a vector space. Also refer to Function space in Linear Algebra as well as to Dualraum (in German). In latter source the more general function space

is indeed a vector space. Also refer to Function space in Linear Algebra as well as to Dualraum (in German). In latter source the more general function space ![]() is introduced.

is introduced.

Let us now have another glimpse on a (finite-dimensional) function vector space.

Example 1.2: (Polynomials of finite degree)

The space of all polynomials with degree less than or equal to ![]() is a finite-dimensional vector space as outlined by Dr. Trefor Bazett. Also check out the following video.

is a finite-dimensional vector space as outlined by Dr. Trefor Bazett. Also check out the following video.

Another video outlines how the concepts of linear independence, span, etc. work in the space of polynomials with finite dimension.

![]()

Infinite Dimensional Function Spaces

Let us start with the most general case.

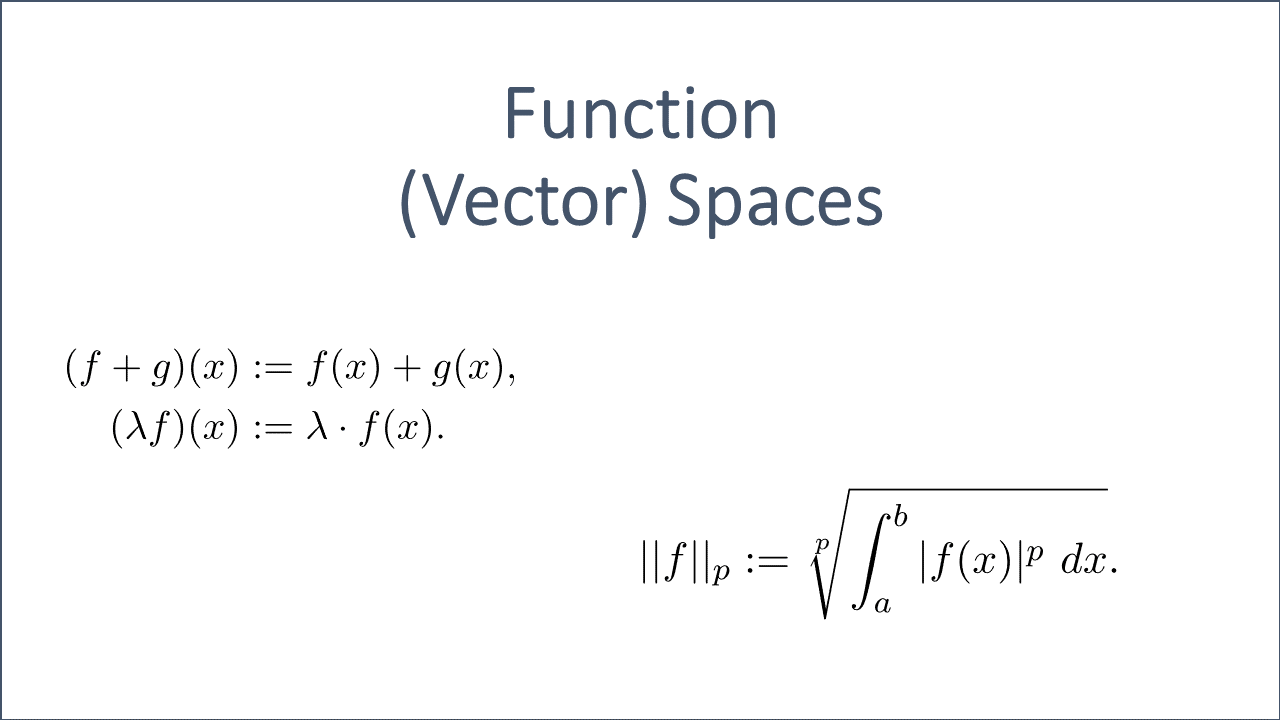

Consider the set ![]() of all functions

of all functions ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() . We define the following operations on

. We define the following operations on ![]() .

.

(1) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} f+g:[a,b] &\rightarrow \mathbb{F}, \text{ defined by } \\ (f+g)(x) &:= f(x)+g(x) \quad \forall x\in [a,b] \\ \lambda f:[a,b] &\rightarrow \mathbb{F}, \text{ defined by } \\ (\lambda f)(x) &:= \lambda f(x) \quad \forall x\in [a,b] \end{align*}](https://www.deep-mind.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-63d83b35c2a0abbd1d26e777e4243f62_l3.png)

We can check that all the axioms of a vector space are fulfilled. Note that ![]() could also be set to

could also be set to ![]() and

and ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

Example 2.1 (Set of all ![]() -valued functions on

-valued functions on ![]() )

)

Let us check that the operations as defined in (1) are closed. If ![]() and

and ![]() then we can form the sum and the result

then we can form the sum and the result ![]() is still a function on the same interval.

is still a function on the same interval.

Due to the fact that the associative property holds true in ![]() and given that

and given that ![]() , we can imply

, we can imply ![]() by using the definition (1).

by using the definition (1).

Hence, ![]() for all

for all ![]() holds true.

holds true.

The null vector is the null function ![]() mapping every element to the zero element of

mapping every element to the zero element of ![]() . Again, just apply the definition of the operation as well as the properties of

. Again, just apply the definition of the operation as well as the properties of ![]() .

.

The additive inverse of ![]() is

is ![]() , such that

, such that ![]() for all

for all ![]() .

.

Apparently, ![]()

![]() holds true for all

holds true for all ![]() .

.

The set of all function ![]() on the interval

on the interval ![]() is therefore an Abelian group. The other axioms can be proved similarly by just using the properties of the field

is therefore an Abelian group. The other axioms can be proved similarly by just using the properties of the field ![]() and the corresponding definition (1).

and the corresponding definition (1).

Thus, the set of all functions ![]() is a vector space.

is a vector space.

![]()

The role of the last example is usually considered to be small due to its generality. However, if we restrict the set ![]() and thus add more structure and corresponding properties, then the situation will drastically change.

and thus add more structure and corresponding properties, then the situation will drastically change.

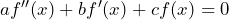

Each of the following sets of functions together with the operations (1) form an interesting and useful vector spaces. These function spaces are used heavily, for instance, in Approximation Theory and Functional Analysis:

- Set of all continuous real functions

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com C[a,b]](https://www.deep-mind.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-c0d94c415f4cf1446218ef5e32dc64ea_l3.png) defined on an interval

defined on an interval ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com [a,b]](https://www.deep-mind.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-a535f6287df84b084711c6e772614d2e_l3.png) ;

; - Set of all polynomials

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \mathbb{R}[X]](https://www.deep-mind.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d771b50a5c37e00828a37632e7c556c6_l3.png) defined on the reals;

defined on the reals; - Set of all differentiable functions

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com D[a,b]](https://www.deep-mind.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-3f39603b17c9a248c3fb6068b0721c93_l3.png) defined on an interval

defined on an interval ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com [a,b]](https://www.deep-mind.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-a535f6287df84b084711c6e772614d2e_l3.png) ;

; - Set of all integrable functions

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com Int[a,b]](https://www.deep-mind.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-db77472185d4ae7595287dd6f4e49344_l3.png) defined on an interval

defined on an interval ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com [a,b]](https://www.deep-mind.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-a535f6287df84b084711c6e772614d2e_l3.png) ;

; - Set of all differentiable functions that are solutions of a differential equation of the form

.

.

Let us consider two concrete examples a bit more detailed.

Example 2.2 (Polynomial & Continuous Function Space)

The space of all polynomials with one variable over the rationals ![]() or the reals

or the reals ![]() as well as the space of all continuous real functions

as well as the space of all continuous real functions ![]() defined on

defined on ![]() ,

, ![]() , are infinite dimensional vector spaces.

, are infinite dimensional vector spaces.

Note that all arguments that have been used in Example 2.1 can be re-used except the closure argument. That is, we only need to show that the sum of two elements and the scalar multiplication lies again in the corresponding function space.

The sum of two continuous real functions defined on ![]() is again a continuous real function on the same domain. This can be proved by using, for instance, the interconnection between continuous functions and the existence of limits. The closure of scalar multiplication can be shown in a similar way.

is again a continuous real function on the same domain. This can be proved by using, for instance, the interconnection between continuous functions and the existence of limits. The closure of scalar multiplication can be shown in a similar way.

The addition of two polynomials ![]() and

and ![]() is again a polynomial of degree

is again a polynomial of degree ![]() . This becomes obvious if you consider a polynomial as a series of its coefficient.

. This becomes obvious if you consider a polynomial as a series of its coefficient.

The vector space is infinite dimensional since ![]() contains polynomials of arbitrary degree. That is, you can find a set of polynomials such as

contains polynomials of arbitrary degree. That is, you can find a set of polynomials such as ![]() that are linearly independent and generates the entire vector space

that are linearly independent and generates the entire vector space ![]() (i.e. it is an infinite basis).

(i.e. it is an infinite basis).

![]()

Let us have an illustrated overview on a collection of the most important facts on the beautiful interplay between linear algebra and analysis provided by Dr. Trefor Bazett.

It is usually helpful to have an intuitive understanding of a mathematical object such as a function space.

Norm / Length of a Function

Inner products and norms enables us to define and apply geometrical terms such as length, distance and angle. These concepts can be very illustrative in the Euclidean space, however, what does the length of a function mean?

Actually, the definition of a norm on a function space is quite similar to what we had on the Euclidean space.

Definition 3.1 (![]() norms on function spaces)

norms on function spaces)

The ![]() norm for functions

norm for functions ![]() is defined by

is defined by

(2) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} ||f||_p := \sqrt[p]{\int_{a}^{b}{|f(x)|^p \ dx}}. \end{align*}](https://www.deep-mind.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-fbc9eef7ccef5e1793a0cce82c08b251_l3.png)

![]()

A ![]() norm can be thought of as the length of

norm can be thought of as the length of ![]() . Let us illustrate the

. Let us illustrate the ![]() norm for functions in the following example.

norm for functions in the following example.

Example 3.1 (![]() norm for functions)

norm for functions)

The ![]() norm on function spaces is defined by

norm on function spaces is defined by

(3) ![]()

for any continuous function ![]() . It is ensured that a continuous and bounded function is integrable. Note, however, that

. It is ensured that a continuous and bounded function is integrable. Note, however, that ![]() not when

not when ![]() but when

but when ![]() almost everywhere. The failure of this axiom, however, can be overcome by defining equivalence classes

almost everywhere. The failure of this axiom, however, can be overcome by defining equivalence classes ![]() . Nonetheless, we are going to use the notation

. Nonetheless, we are going to use the notation ![]() while keeping in mind that for the

while keeping in mind that for the ![]() norm this is actually an equivalence class. Refer to Remark 2.23 in [1] for further details.

norm this is actually an equivalence class. Refer to Remark 2.23 in [1] for further details.

Let us now look at simple example to better understand the heuristic. To this end, we set ![]() .

.

![]()

So the length of a constant function on ![]() using the

using the ![]() norm is exactly

norm is exactly ![]() . The length of the function

. The length of the function ![]() with

with ![]() is

is

![]()

Apparently, the length of the function can somehow be associated with the area under the function graph. Hence, if we extend the integral to ![]() , we get for the function the following:

, we get for the function the following:

![]()

![]()

The approximation of functions is a very crucial technique, that is used not only in Analysis, Numerical Math and Computer Science. Just think about how continuous functions such as the ![]() function is calculated in the computer you are using.

function is calculated in the computer you are using.

If we need to approximate a function ![]() with a function

with a function ![]() , it is therefore of great importance to have a measure of “closeness” between these two functions. We can simply use definition (3) and slightly modify it to get a suitable measure of closeness between two suitable functions.

, it is therefore of great importance to have a measure of “closeness” between these two functions. We can simply use definition (3) and slightly modify it to get a suitable measure of closeness between two suitable functions.

(4) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} ||f-g||_p := \sqrt[p]{\int_{a}^{b}{|(f-g)(x)|^p \ dx}}. \end{align*}](https://www.deep-mind.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-8a0774bd0f0a10aa88068cd6ea7a6709_l3.png)

Please also refer to the following video for a nice illustration of these concepts.

norms for function spaces

norms for function spacesIn functional analysis, where Banach spaces are studied, the features of metrics and norms are of utter importance. For instance, the completeness of these function spaces play a crucial role as outlined in Banach and Fréchet spaces of functions.

Literature

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]